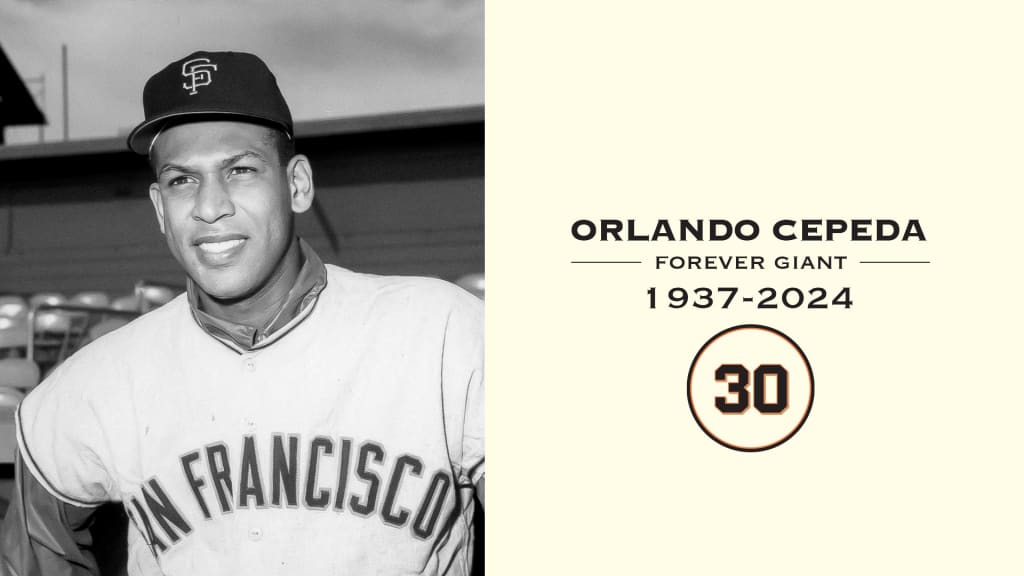

Hall of Fame first baseman Orlando Cepeda, who left an indelible stamp of excellence on two National League franchises during the 1960s, died Friday, the Giants announced. He was 86.

“Our beloved Orlando passed away peacefully at home this evening, listening to his favorite music and surrounded by his loved ones,” his wife, Nydia, said in a statement released by the Giants. “We take comfort that he is at peace.”

“We lost a true gentleman and legend,” Giants chairman Greg Johnson said. “Orlando was a great ambassador for the game throughout his playing career and beyond. He was one of the all-time great Giants and he will truly be missed. Our condolences go out to the Cepeda family for their tremendous loss and we extend our thoughts to Orlando’s teammates, his friends, and to all those touched by his passing.”

The Baby Bull 🧡 pic.twitter.com/bGjvy0jbRg

— SFGiants (@SFGiants) June 29, 2024

“This is truly a sad day for the San Francisco Giants,’’ Giants president and chief executive officer Larry Baer said. “For all of Orlando’s extraordinary baseball accomplishments, it was his generosity, kindness and joy that defined him. No one loved the game more. Our heartfelt condolences go out to his wife, Nydia, his five children, Orlando, Jr., Malcolm, Ali, Carl and Hector, his nine grandchildren, his one great granddaughter as well as his extended family and friends.”

Cepeda emerged as a key figure as baseball became a coast-to-coast pastime when the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers moved to San Francisco and Los Angeles, respectively, before the 1958 season.

Traded to St. Louis during the 1966 season, “The Baby Bull” won the National League Most Valuable Player award the following year and was heavily responsible for the Cardinals’ back-to-back pennant-winning seasons in 1967-68.

Legend has it that Giants player-coach Whitey Lockman approached manager Bill Rigney during big league camp in Spring Training 1958 and said of Cepeda, “Too bad the kid’s a year away.”

“Away from what?” Rigney asked.

“From the Hall of Fame,” replied Lockman, aware that Cepeda had not yet played a regular-season game in the Majors.

Cepeda excelled immediately. He earned NL Rookie of the Year honors following the Giants’ inaugural season in California, when he hit .312 with 25 home runs, 96 RBIs and an NL-high 38 doubles.

Cepeda remained one of baseball’s most ferocious hitters. He totaled at least 24 homers in each of his first seven seasons (1958-64) with the Giants. His 222 home runs during this span ranked 10th in the Major Leagues. Among the few who eclipsed Cepeda’s total were seven sluggers who ultimately surpassed the 500-homer plateau: Willie Mays, Harmon Killebrew, Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Ernie Banks, Frank Robinson and Eddie Mathews.

“What another gut punch,” Giants manager Bob Melvin said. “Another incredible personality. Just beloved here, the statue out front. The numbers he put up. There are a lot of legends here. He was certainly right in the middle of that. To have it so close in proximity to Willie, it’s kind of staggering.”

The Baby Bull is a true #ForeverGiant 🧡 pic.twitter.com/gLy6JoT7X4

— SFGiants (@SFGiants) June 29, 2024

The genial Cepeda quickly became a fan favorite in San Francisco. To a degree, his popularity developed at the expense of Mays, the incomparable center fielder who drew scorn from provincially minded fans simply because he came from New York with the franchise. By contrast, those same fans viewed Cepeda as one of their own because he and the ballclub arrived in San Francisco simultaneously. His enthusiasm for San Francisco night life, particularly jazz clubs, further endeared him to the public.

The second native of Puerto Rico to be elected to the Hall of Fame, after Roberto Clemente, Cepeda also was at the forefront of the growing presence of Latin American athletes in the Majors. Given sports’ tendency to imitate life and America’s turbulent race relations in the ’60s, Cepeda occasionally found himself in unpleasant situations. In a game against Cincinnati, Cepeda and Giants teammate Jose Pagan were on base discussing strategy in Spanish. The pitcher hollered, “Speak English. You’re in America now.” Cepeda retorted, “English? OK,” followed by a couple of expletives.

As the ’60s elapsed, the Giants encountered a rare problem: Possessing too much talent. They struggled to find ways to keep Cepeda in the lineup along with Willie McCovey, another power-hitting first baseman. McCovey captured NL Rookie of the Year honors in 1959, one year after Cepeda.

McCovey performed erratically during the following two seasons. But after he hit 20 homers in only 262 plate appearances in 1962, the Giants realized that they couldn’t keep him on the bench. McCovey started 130 games in left field in 1963 and tied for the NL lead with 44 homers.

A lingering knee injury limited Cepeda to 40 plate appearances in 33 games in 1965. Always seeking pitching depth to complement their powerful lineups, the Giants shipped Cepeda to St. Louis for left-hander Ray Sadecki on May 8, 1966.

The St. Louis Cardinals offer our condolences to the family and friends of Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda who sadly passed away earlier this evening at the age 86.

Orlando brought his love for life and the game of baseball to St. Louis in 1966, and enjoyed an MVP season the… pic.twitter.com/IDIov0uuOE

— St. Louis Cardinals (@Cardinals) June 29, 2024

Many Giants fans regard the trade as the worst one in the club’s history. Sadecki, a 20-game winner in 1964, went 3-7 for the Giants in ’66 as they finished 1 1/2 games behind the first-place Dodgers in the NL standings. One year later, Cepeda was the league’s unanimous choice for MVP as he hit .325 with 25 homers and 111 RBIs for the Cardinals, who finished 10 1/2 games in front of the second-place Giants. St. Louis proceeded to edge Boston in a seven-game World Series.

Cardinals catcher Tim McCarver recalled waiting on the team bus before a ride to New York’s Shea Stadium for a ballgame. Every member of the team was aboard except for Cepeda. The bus was about to depart when Bob Gibson, the team’s ace right-hander and a future Hall of Famer, ordered the driver to halt. Said Gibson, who was pitching that day, “This bus isn’t going anywhere without Orlando” — a tribute to Cepeda’s presence in the lineup.

Despite the respect Cepeda commanded, St. Louis dealt him to Atlanta on March 17, 1969, for third baseman Joe Torre. Cepeda’s first two seasons in Atlanta were productive ones. He amassed 22 homers and 88 RBIs to help Atlanta win the NL West in 1969, then batted .305 with 34 homers and 111 RBIs in 1970.

Cepeda had one more big year left in him. One of the first players to serve exclusively as a designated hitter, Cepeda took advantage of its inception in 1973 to hit .289 with 20 homers and 86 RBIs for Boston. He was named the American League’s Designated Hitter of the Year. Cepeda retired after the 1974 season, when he hit .215 with one homer and 18 RBIs for Kansas City. His statistics in a career that spanned 17 seasons featured a .297 batting average, 379 home runs, 1,365 RBIs, a .350 on-base percentage and a .499 slugging percentage.

“He was a gentleman,” said Dodgers manager Dave Roberts, whose team was playing in San Francisco when the Giants announced Cepeda’s death. “I don’t think there’s anyone in baseball that can say a bad word about Orlando. To lose two baseball greats, two great Giants … there was a somberness in the stadium tonight.”

Orlando Manuel Cepeda Pennes was born on Sept. 17, 1937, in Ponce, Puerto Rico. His father, Pedro, nicknamed Perucho, gained renown as a professional ballplayer in a Puerto Rican league. Inevitably drawn to baseball, the younger Cepeda joined the Giants organization as one of the many Latin American players discovered by famed scout Alex Pompez.

Originally signed as a third baseman entering the 1955 season, Cepeda moved across the diamond one year later. This was far from the most challenging transition he faced. Like most Latin American players, Cepeda did not speak English; nor did he understand the racist Jim Crow laws in effect throughout most southern Minor League towns — including Salem, Va., where the Giants initially sent him. He was transferred to another Class D squad in Kokomo and finished the season with a .364 batting average, 22 homers and 91 RBIs overall. Promoted to Class C the next year, Cepeda won the Northwest League Triple Crown with a .355 batting average, 26 homers and 112 RBIs. Though he spent another year in the Minors, he was clearly ready for the big leagues.

Cepeda wasn’t blindly grateful to the Giants. He clashed with general manager Chub Feeney over his salary and with manager Alvin Dark over his insistence that Latin players speak English in the clubhouse.

In 1978, Cepeda was convicted of marijuana possession, a charge stemming from a 1975 incident. He spent 10 months of a five-year sentence in a Puerto Rican jail before serving the rest of his sentence on probation.

Cepeda rejoined the Giants organization after attending a 1987 fantasy camp. He scouted for the organization in Latin American countries before returning to northern California to serve the team in community relations, a post he held until his death.

Cepeda became eligible for election to the Hall of Fame in 1980. He never came close to receiving the 75 percent of the electorate needed for induction until 1994, his final year on the ballot, when the Giants and other supporters launched a campaign on his behalf. He received a vote total of 73.5 percent, seven votes shy of election. The Veterans Committee elected him to Cooperstown in 1999.

That same year, the Giants retired Cepeda’s jersey number, 30. On Sept. 6, 2008, the club unveiled and dedicated a nine-foot-tall statue of Cepeda outside of Oracle Park. Unlike the sculptures of the other San Francisco-era Hall of Famers, who are depicted hitting or throwing, Cepeda’s bronze image is standing and smiling, about to throw a ball for a game of catch.